Amproprification #5: Goldrausch, Mark Lorenz Kysela

Finished 2017

for Soprano Saxophone and automated amplification

duration:

40'

Right from the beginning, [Mark Lorenz Kysela's] Goldrausch was conceived in connection with the principle of amproprification. Maximilian Marcoll’s concept of amproprification contains both appropriation and amplification. Appropriation because Marcoll appropriates the works of others, daring to impose something new on the work. Amplification because the only change Marcoll makes concerns volume.

Marcoll first chooses a work to be amproprified, usually one he particularly values. He records all the respective piece’s parts separately and then develops for each part its own volume curve with its own amplification values. In concert, the individual parts are then amplified with these volume curves.

So far, this has been done with works by Ludwig van Beethoven, Peter Ablinger, Franco Donatoni, Gabriel Fauré and Michael Maierhof amongst others. First and foremost, it is important that the original remains intact as the basis of amproprification. Marcoll doesn’t regard his adaptation as painting over the original, but as a transformation in which individual aspects of the original stand out.

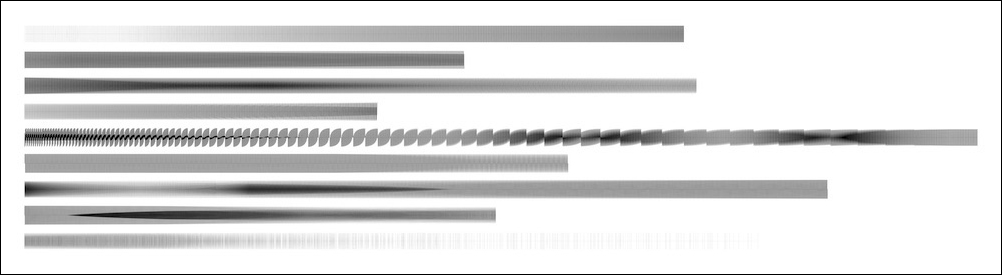

At the same time, the volume changes can drastically change the original. In some cases, Marcoll’s intervention comes across as a malfunction. For example, in the recording of his Fauré Amproprification you might even believe that your stereo system was defective, while the visualisation of the interventions is reminiscent of Oskar Fischinger’s graphic processing of soundtracks, or the works of Op Art.

Amproprification #5: Goldrausch is an exception insofar as it is not the concert performance of the work that is changed here, but the recording of a piece. Marcoll has opted for two interventions, which have a very radical effect on the original.

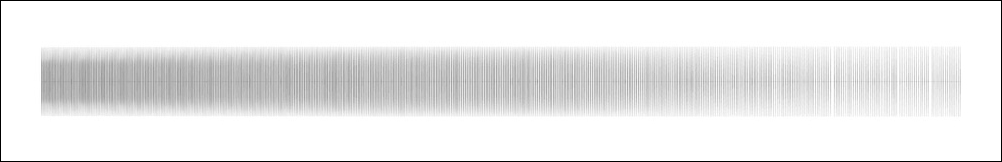

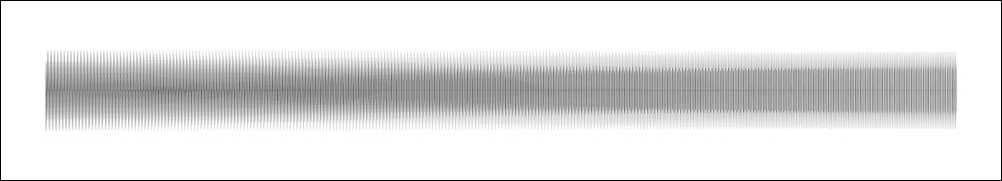

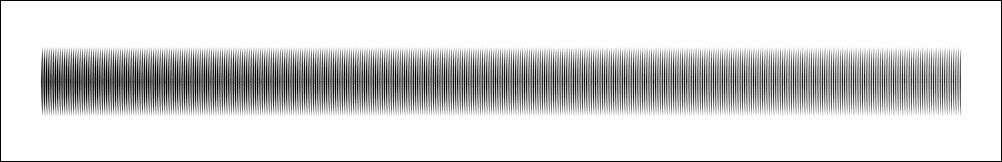

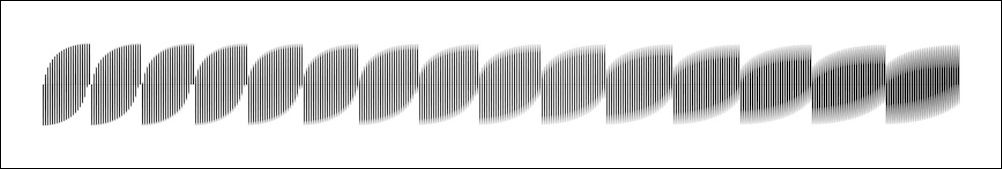

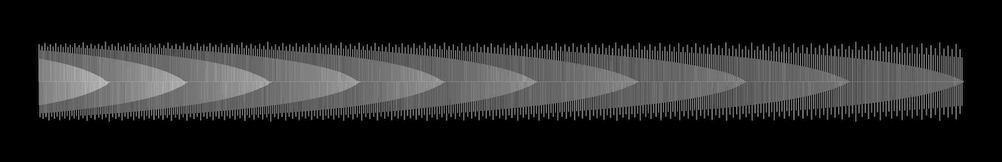

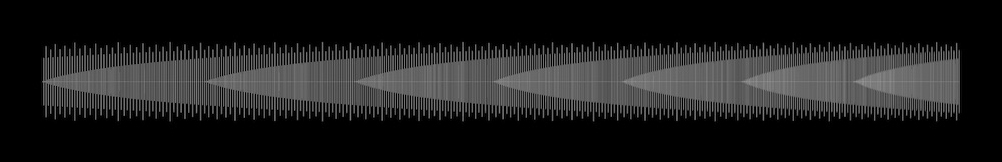

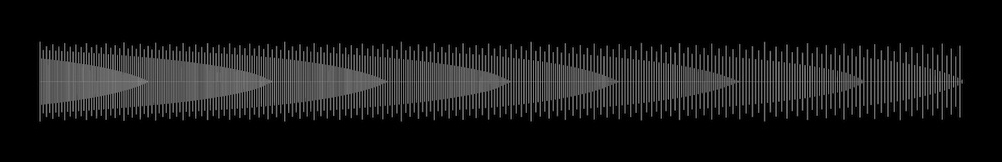

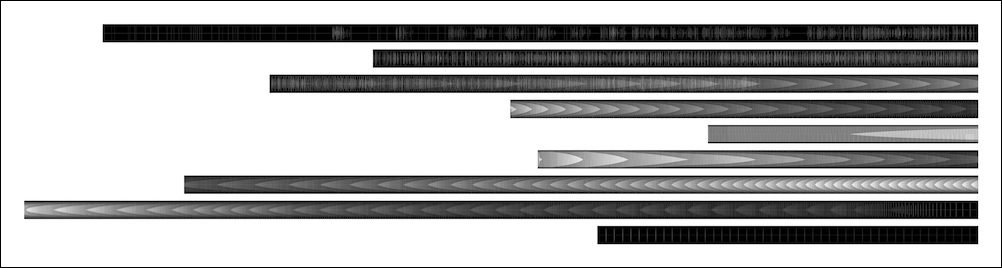

In the A-section, Kysela’s recording is amplitude modulated at a frequency of 9 Hz, i.e. turned on and off nine times per second. In the B-section, the frequency of this modulation is changed, first in an accelerando, until only a rattling whirring remains, then in a ritardando until the piece ends at a frequency of 0.55 Hz, the speed the record player spins.

In doing so, Marcoll interweaves the accelerandi and the ritardandi to create the illusion of endless acceleration and deceleration (a method known as Shepard or Risset glissandi on ascending or descending scales).

Marcoll’s idea was to counter Kysela’s flat noise with the impulse, in other words, with a completely different quality. (In the pioneering age of electronic music, noise and impulse together with the sine tone, were counted among the basic elements of electronic music.)

It is worth noting in Amproprification #5 that Marcoll’s very systematic intervention acts very rigorously on the original. Even the beginning, which seems almost like minimal techno or glitch, makes it clear that the transformation also represents a qualitative intervention in the substance of the original. Nevertheless, Kysela’s sound persists. Not only is it recognisable beneath the surface, but one also has the impression that Marcoll could not compose this music without Kysela’s flat noise. However, Marcoll emphasises the synthetic and the disembodied qualities in the music. What is defined as a contradiction in Kysela’s work is resolved in Marcoll’s in favour of the artificial.

Björn Gottstein

Translation: Katherine Wren

Past Performances:

Oct 5th, 2018

Morelia (MEX), CMMAS, Amproprifications

Feb 3rd, 2018

Stuttgart, Theaterhaus, stock11 – Nachtkonzert 3: GlinggGlingg @ Eclat

Nov 9th, 2017

Berlin, Galerie im Ratskeller, Berlin Lichtenberg, ECHOES, Meet the artist, with M. L. Kysela

Nov 5th, 2017

Berlin, Studio8, sacredrealism, with M. L. Kysela

Dec 9th, 2016

OE1, ORF, Radio, stock11 @ Compromise – Wien Modern

Nov 20th, 2016

Vienna, Brick 5, stock11 @ Comprovise – Wien Modern

Oct 27th, 2016

Oldenburg, Schloss, Oh Ton Festival